Difference between revisions of "Directory:Jon Awbrey/Papers/Differential Analytic Turing Automata"

Jon Awbrey (talk | contribs) (→Output: markup) |

Jon Awbrey (talk | contribs) (update) |

||

| (21 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:Differential Analytic Turing Automata}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:Differential Analytic Turing Automata}} | ||

| + | '''Author: [[User:Jon Awbrey|Jon Awbrey]]''' | ||

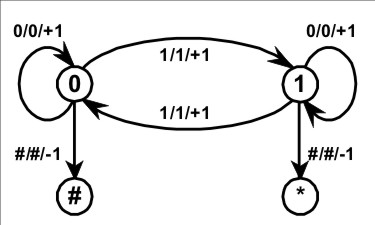

| − | + | The task ahead is to chart a course from general ideas about ''transformational equivalence classes of graphs'' to a notion of ''differential analytic turing automata'' (DATA). It may be a while before we get within sight of that goal, but it will provide a better measure of motivation to name the thread after the envisioned end rather than the more homely starting place. | |

| − | + | The basic idea is as follows. One has a set <math>\mathcal{G}</math> of graphs and a set <math>\mathcal{T}</math> of transformation rules, and each rule <math>\mathrm{t} \in \mathcal{T}</math> has the effect of transforming graphs into graphs, <math>\mathrm{t} : \mathcal{G} \to \mathcal{G}.</math> In the cases that we shall be studying, this set of transformation rules partitions the set of graphs into ''transformational equivalence classes'' (TECs). | |

| − | |||

| − | The basic idea | ||

There are many interesting excursions to be had here, but I will focus mainly on logical applications, and and so the TECs I talk about will almost always have the character of ''logical equivalence classes'' (LECs). | There are many interesting excursions to be had here, but I will focus mainly on logical applications, and and so the TECs I talk about will almost always have the character of ''logical equivalence classes'' (LECs). | ||

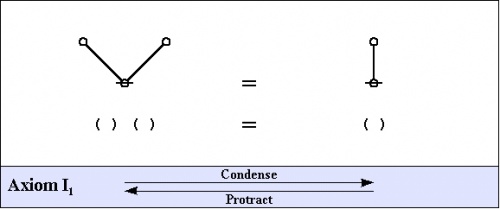

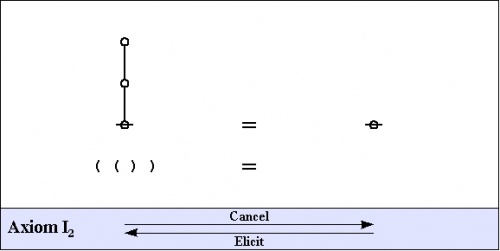

| − | An example that will figure heavily in the sequel is given by rooted trees as the species of graphs and a pair of equational transformation rules that derive from the graphical calculi of | + | An example that will figure heavily in the sequel is given by rooted trees as the species of graphs and a pair of equational transformation rules that derive from the graphical calculi of C.S. Peirce, as revived and extended by George Spencer Brown. |

Here are the fundamental transformation rules, also referred to as the ''arithmetic axioms'', more precisely, the ''arithmetic initials''. | Here are the fundamental transformation rules, also referred to as the ''arithmetic axioms'', more precisely, the ''arithmetic initials''. | ||

| Line 21: | Line 20: | ||

That should be enough to get started. | That should be enough to get started. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Cactus Language== |

I will be making use of the ''cactus language'' extension of Peirce's Alpha Graphs, so called because it uses a species of graphs that are usually called "cacti" in graph theory. The last exposition of the cactus syntax that I've written can be found here: | I will be making use of the ''cactus language'' extension of Peirce's Alpha Graphs, so called because it uses a species of graphs that are usually called "cacti" in graph theory. The last exposition of the cactus syntax that I've written can be found here: | ||

| − | :* [ | + | :* [[Propositional Equation Reasoning Systems|Propositional Equation Reasoning Systems (PERS)]] |

The representational and computational efficiency of the cactus language for the tasks that are usually associated with boolean algebra and propositional calculus makes it possible to entertain a further extension, to what we may call ''differential logic'', because it develops this basic level of logic in the same way that differential calculus augments analytic geometry to handle change and diversity. There are several different introductions to differential logic that I have written and distributed across the Internet. You might start with the following couple of treatments: | The representational and computational efficiency of the cactus language for the tasks that are usually associated with boolean algebra and propositional calculus makes it possible to entertain a further extension, to what we may call ''differential logic'', because it develops this basic level of logic in the same way that differential calculus augments analytic geometry to handle change and diversity. There are several different introductions to differential logic that I have written and distributed across the Internet. You might start with the following couple of treatments: | ||

| Line 32: | Line 31: | ||

:* [http://stderr.org/pipermail/inquiry/2004-February/thread.html#1160 Differential Logic B] | :* [http://stderr.org/pipermail/inquiry/2004-February/thread.html#1160 Differential Logic B] | ||

| − | I | + | I will draw on those previously advertised resources of notation and theory as needed, but right now I sense the need for some concrete examples. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Example 1== | |

| − | Let's say we have a system that is known by the name of its state space <math>X\!</math> and we have a boolean state variable <math>x : X \to \mathbb{B},</math> where <math>\mathbb{B} = \{ 0, 1 \}.</math> | + | Let's say we have a system that is known by the name of its state space <math>X\!</math> and we have a boolean state variable <math>x : X \to \mathbb{B},\!</math> where <math>\mathbb{B} = \{ 0, 1 \}.\!</math> |

We observe <math>X\!</math> for a while, relative to a discrete time frame, and we write down the following sequence of values for <math>x.\!</math> | We observe <math>X\!</math> for a while, relative to a discrete time frame, and we write down the following sequence of values for <math>x.\!</math> | ||

| Line 44: | Line 41: | ||

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <math>\begin{array}{ | + | <math>\begin{array}{c|c} |

| − | t & x \\ | + | t & x \\[8pt] |

| − | |||

0 & 0 \\ | 0 & 0 \\ | ||

1 & 1 \\ | 1 & 1 \\ | ||

| Line 60: | Line 56: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | “Aha!” we say, and think we see the way of things, writing down the rule <math>x' = \texttt{(} x \texttt{)},\!</math> where <math>x'\!</math> is the next state after <math>x\!</math> and <math>\texttt{(} x \texttt{)}\!</math> is the negation of <math>x\!</math> in boolean logic. | |

Another way to detect patterns is to write out a table of finite differences. For this example, we would get: | Another way to detect patterns is to write out a table of finite differences. For this example, we would get: | ||

| Line 66: | Line 62: | ||

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <math>\begin{array}{ | + | <math>\begin{array}{c|cccc} |

| − | t & | + | t & x & \mathrm{d}x & \mathrm{d}^2 x & \ldots \\[8pt] |

| − | + | 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & \ldots \\ | |

| − | 0 & | + | 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & \ldots \\ |

| − | 1 & | + | 2 & 0 & 1 & 0 & \ldots \\ |

| − | 2 & | + | 3 & 1 & 1 & 0 & \ldots \\ |

| − | 3 & | + | 4 & 0 & 1 & 0 & \ldots \\ |

| − | 4 & | + | 5 & 1 & 1 & 0 & \ldots \\ |

| − | 5 & | + | 6 & 0 & 1 & 0 & \ldots \\ |

| − | 6 & | + | 7 & 1 & 1 & 0 & \ldots \\ |

| − | 7 & | + | 8 & 0 & 1 & \ldots & \ldots \\ |

| − | 8 & | + | 9 & \ldots & \ldots & \ldots & \ldots |

| − | 9 & \ldots & \ldots & \ldots & | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 84: | Line 79: | ||

And of course, all the higher order differences are zero. | And of course, all the higher order differences are zero. | ||

| − | This leads to thinking of <math>X\!</math> as having an extended state <math>(x, | + | This leads to thinking of <math>X\!</math> as having an extended state <math>(x, \mathrm{d}x, \mathrm{d}^2 x, \ldots, \mathrm{d}^k x),\!</math> and this additional language gives us the facility of describing state transitions in terms of the various orders of differences. For example, the rule <math>x' = \texttt{(} x \texttt{)}\!</math> can now be expressed by the rule <math>{\mathrm{d}x = 1}.\!</math> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | There is a more detailed account of differential logic in the following paper: | |

| − | :* [[ | + | :* [[Differential Logic and Dynamic Systems 2.0|Differential Logic and Dynamic Systems]] |

| − | For future reference, here are a couple of handy rosetta stones for translating back and forth between different notations for the boolean functions <math>f : \mathbb{B}^k \to \mathbb{B},</math> where <math>k = 1, 2.\!</math> | + | For future reference, here are a couple of handy rosetta stones for translating back and forth between different notations for the boolean functions <math>f : \mathbb{B}^k \to \mathbb{B},\!</math> where <math>k = 1, 2.\!</math> |

| − | :* [[ | + | :* [[Differential Logic and Dynamic Systems 2.0#Tables of Propositional Forms|Tables of Propositional Forms]] |

| − | == | + | ==Example 2== |

| − | For a slightly more interesting example, let's suppose that we have a dynamic system that is known by its state space <math>X | + | For a slightly more interesting example, let's suppose that we have a dynamic system that is known by its state space <math>X\!</math> and we have a boolean state variable <math>x : X \to \mathbb{B}.\!</math> In addition, we are given an initial condition <math>x = \mathrm{d}x\!</math> and a law <math>{\mathrm{d}^2 x = \texttt{(} x \texttt{)}}.\!</math> |

The initial condition has two cases: | The initial condition has two cases: | ||

| Line 107: | Line 98: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{ll} | <math>\begin{array}{ll} | ||

| − | 1. & | + | 1. & x ~=~ \mathrm{d}x ~=~ 0 |

\\ | \\ | ||

| − | 2. & | + | 2. & x ~=~ \mathrm{d}x ~=~ 1 |

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Here is a table of the two trajectories or ''orbits'' that we get by starting from each of the two permissible initial states and staying within the constraints of the dynamic law <math> | + | Here is a table of the two trajectories or ''orbits'' that we get by starting from each of the two permissible initial states and staying within the constraints of the dynamic law <math>{\mathrm{d}^2 x = \texttt{(} x \texttt{)}}.\!</math> |

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | ||

| − | | <math>\text{Initial State}\ x \ | + | | <math>\text{Initial State}~ x \cdot \mathrm{d}x\!</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <math>\begin{array}{ | + | <math>\begin{array}{c|ccc} |

| − | t & | + | t & \mathrm{d}^0 x & \mathrm{d}^1 x & \mathrm{d}^2 x \\[8pt] |

| − | + | 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\ | |

| − | 0 & | + | 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ |

| − | 1 & | + | 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ |

| − | 2 & | + | 3 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ |

| − | 3 & | + | 4 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ |

| − | 4 & | + | 5 & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel |

| − | 5 & | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 134: | Line 124: | ||

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | ||

| − | | <math>\text{Initial State}\ (x) \cdot ( | + | | <math>\text{Initial State}~ \texttt{(} x \texttt{)} \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}x \texttt{)}\!</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <math>\begin{array}{ | + | <math>\begin{array}{c|ccc} |

| − | t & | + | t & \mathrm{d}^0 x & \mathrm{d}^1 x & \mathrm{d}^2 x \\[8pt] |

| − | + | 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ | |

| − | 0 & | + | 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ |

| − | 1 & | + | 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ |

| − | 2 & | + | 3 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ |

| − | 3 & | + | 4 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ |

| − | 4 & | + | 5 & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel |

| − | 5 & | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Note that the state <math>\ | + | Note that the state <math>x \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}x \texttt{)(} \mathrm{d}^2 x \texttt{)},\!</math> that is, <math>(x, \mathrm{d}x, \mathrm{d}^2 x) = (1, 0, 0),\!</math> is a stable attractor for both orbits. |

Further discussion of this example, complete with charts and graphs, can be found at this location: | Further discussion of this example, complete with charts and graphs, can be found at this location: | ||

| − | :* [[ | + | :* [[Differential Logic and Dynamic Systems 2.0#Example 1. A Square Rigging|Example 1. A Square Rigging]] |

| − | == | + | ==Example 3== |

| − | One more example may serve to suggest just how much dynamic complexity can be built on a universe of discourse that has but a single logical feature at its base. | + | One more example may serve to suggest just how much dynamic complexity can be built on a universe of discourse that has but a single logical feature at its base. But first, there are a few more elements of general notation that that we'll need to describe finite dimensional universes of discourse and the qualitative dynamics that we envision occurring in them. |

| − | + | Let <math>\mathcal{X} = \{ x_1, \ldots, x_n \}\!</math> be the ''alphabet'' of logical ''features'' or ''variables'' that are used to describe the <math>n\!</math>-dimensional universe of discourse <math>X^\bullet = [\mathcal{X}]\!</math> <math>= [x_1, \ldots, x_n].\!</math> One may picture a venn diagram whose <math>n\!</math> overlapping “circles” are labeled with the feature names in <math>\mathcal{X}.\!</math> Staying with this picture, one visualizes the universe of discourse <math>X^\bullet = [\mathcal{X}]\!</math> as having two layers: | |

| − | + | # The set <math>X = \langle \mathcal{X} \rangle = \langle x_1, \dots, x_n \rangle\!</math> of ''points'' or ''cells'' — the latter used in another sense of the word than when we speak of ''cellular automata''. | |

| + | # The set <math>X^\uparrow = (X \to \mathbb{B})\!</math> of ''propositions'', boolean-valued functions, or maps from <math>X\!</math> to <math>\mathbb{B}.\!</math> | ||

| − | Thus | + | Thus we picture the universe of discourse <math>{X^\bullet}\!</math> as an ordered pair <math>{X^\bullet = (X, X^\uparrow)}\!</math> having <math>2^n\!</math> points in the underlying space <math>X\!</math> and <math>2^{2^n}\!</math> propositions in the function space <math>X^\uparrow.\!</math> |

A more complete discussion of these notations can be found here: | A more complete discussion of these notations can be found here: | ||

| − | :* [[ | + | :* [[Differential Logic and Dynamic Systems 2.0#A Functional Conception of Propositional Calculus|A Functional Conception of Propositional Calculus]] |

Now, to the Example. | Now, to the Example. | ||

| − | Once again, let us begin with a 1-feature alphabet <math>\mathcal{X} = \{ x_1 \} = \{ x \}.</math> In the discussion that follows I will consider a class of trajectories that are ruled by the constraint that <math>d^k x = 0\!</math> for all <math>k\!</math> greater than some fixed <math>m | + | Once again, let us begin with a 1-feature alphabet <math>\mathcal{X} = \{ x_1 \} = \{ x \}.\!</math> In the discussion that follows I will consider a class of trajectories that are ruled by the constraint that <math>\mathrm{d}^k x = 0\!</math> for all <math>k\!</math> greater than some fixed <math>m\!</math> and I will indulge in the use of some picturesque language to describe salient classes of such curves. Given the finite order condition, there is a highest order non-zero difference <math>\mathrm{d}^m x\!</math> that is exhibited at each point in the course of any determinate trajectory. Relative to any point of the corresponding orbit or curve, let us call this highest order differential feature <math>\mathrm{d}^m x\!</math> the ''drive'' at that point. Curves of constant drive <math>\mathrm{d}^m x\!</math> are then referred to as ''<math>m^\text{th}\!</math> gear curves''. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | One additional piece of notation will be needed here. Starting from the base alphabet <math>\mathcal{X} = \{ x \},\!</math> we define and notate <math>\mathrm{E}^j \mathcal{X} = \{ x, \mathrm{d}^1 x, \mathrm{d}^2 x, \ldots, \mathrm{d}^j x \}\!</math> as the ''<math>j^\text{th}\!</math> order extended alphabet over <math>\mathcal{X}.\!</math>'' | |

| − | + | Let us now consider the family of 4<sup>th</sup> gear curves through the extended space <math>\mathrm{E}^4 X = \langle x, \mathrm{d}x, \mathrm{d}^2 x, \mathrm{d}^3 x, \mathrm{d}^4 x \rangle.\!</math> These are the trajectories that are generated subject to the law <math>\mathrm{d}^4 x = 1,\!</math> where it is understood in making such a statement that all higher order differences are equal to <math>0.\!</math> | |

| − | + | Since <math>\mathrm{d}^4 x\!</math> and all higher order <math>\mathrm{d}^j x\!</math> are fixed, the entire dynamics can be plotted in the extended space <math>\mathrm{E}^3 X = \langle x, \mathrm{d}x, \mathrm{d}^2 x, \mathrm{d}^3 x \rangle.\!</math> Thus, there is just enough room in a planar venn diagram to plot both orbits and to show how they partition the points of <math>\mathrm{E}^3 X.\!</math> As it turns out, there are exactly two possible orbits, of eight points each, as illustrated in Figures 16-a and 16-b. See here: | |

| − | + | :* [[Differential Logic and Dynamic Systems 2.0#Example 2. Drives and Their Vicissitudes|Example 2. Drives and Their Vicissitudes]] | |

| − | Here are the < | + | Here are the 4<sup>th</sup> gear curves over the 1-feature universe <math>X = \langle x \rangle\!</math> arranged in the form of tabular arrays, listing the extended state vectors <math>(x, \mathrm{d}x, \mathrm{d}^2 x, \mathrm{d}^3 x, \mathrm{d}^4 x)\!</math> as they occur in one cyclic period of each orbit. |

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | ||

| Line 190: | Line 178: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{c|ccccc} | <math>\begin{array}{c|ccccc} | ||

| − | t & d^0 x & d^1 x & d^2 x & d^3 x & d^4 \\ | + | t & \mathrm{d}^0 x & \mathrm{d}^1 x & \mathrm{d}^2 x & \mathrm{d}^3 x & \mathrm{d}^4 x \\ |

\\ | \\ | ||

| − | 0 & | + | 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ |

| − | 1 & | + | 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ |

| − | 2 & | + | 2 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 \\ |

| − | 3 & | + | 3 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ |

| − | 4 & | + | 4 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ |

| − | 5 & | + | 5 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ |

| − | 6 & | + | 6 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 \\ |

| − | 7 & | + | 7 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 |

| − | \end{array}</math | + | \end{array}</math> |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 210: | Line 198: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{c|ccccc} | <math>\begin{array}{c|ccccc} | ||

| − | t & d^0 x & d^1 x & d^2 x & d^3 x & d^4 \\ | + | t & \mathrm{d}^0 x & \mathrm{d}^1 x & \mathrm{d}^2 x & \mathrm{d}^3 x & \mathrm{d}^4 x \\ |

\\ | \\ | ||

| − | 0 & | + | 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ |

| − | 1 & | + | 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ |

| − | 2 & | + | 2 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 1 \\ |

| − | 3 & | + | 3 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ |

| − | 4 & | + | 4 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ |

| − | 5 & | + | 5 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ |

| − | 6 & | + | 6 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 1 \\ |

| − | 7 & | + | 7 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 |

| − | \end{array}</math | + | \end{array}</math> |

|} | |} | ||

| − | In this arrangement, the temporal ordering of states can be reckoned by a kind of ''parallel round-up rule''. Specifically, if <math>(a_k, a_{k+1})\!</math> is any pair of adjacent digits in a state vector <math>(a_0, a_1, \ldots, a_n),\!</math> then the value of <math>a_k\!</math> in the next state is <math>a_k | + | In this arrangement, the temporal ordering of states can be reckoned by a kind of ''parallel round-up rule''. Specifically, if <math>(a_k, a_{k+1})\!</math> is any pair of adjacent digits in a state vector <math>{(a_0, a_1, \ldots, a_n)},\!</math> then the value of <math>a_k\!</math> in the next state is <math>a_k' = a_k + a_{k+1},\!</math> the addition being taken mod 2, of course. |

A more complete discussion of this arrangement is given here: | A more complete discussion of this arrangement is given here: | ||

| − | :* [[ | + | :* [[Differential Logic and Dynamic Systems 2.0#Example 2. Drives and Their Vicissitudes|Example 2. Drives and Their Vicissitudes]] |

| − | == | + | ==Example 4== |

I am going to tip-toe in silence/consilience past many questions of a philosophical nature/nurture that might be asked at this juncture, no doubt to revisit them at some future opportunity/importunity, however the cases happen to align in the course of their inevitable fall. | I am going to tip-toe in silence/consilience past many questions of a philosophical nature/nurture that might be asked at this juncture, no doubt to revisit them at some future opportunity/importunity, however the cases happen to align in the course of their inevitable fall. | ||

| − | Instead, let's | + | Instead, let's follow the adage to “keep it concrete and simple”, taking up the consideration of an incrementally more complex example, but having a slightly more general character than the orders of sequential transformations that we've been discussing up to this point. |

The types of logical transformations that I have in mind can be thought of as ''transformations of discourse'' because they map a universe of discourse into a universe of discourse by way of logical equations between the qualitative features or logical variables in the source and target universes. | The types of logical transformations that I have in mind can be thought of as ''transformations of discourse'' because they map a universe of discourse into a universe of discourse by way of logical equations between the qualitative features or logical variables in the source and target universes. | ||

| Line 241: | Line 229: | ||

Onward and upward to Flatland, the differential analysis of transformations between 2-dimensional universes of discourse. | Onward and upward to Flatland, the differential analysis of transformations between 2-dimensional universes of discourse. | ||

| − | Consider the transformation from the universe <math>U^\ | + | Consider the transformation from the universe <math>U^\bullet = [u, v]</math> to the universe <math>X^\bullet = [x, y]</math> that is defined by this system of equations: |

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <math>\begin{ | + | <math>\begin{matrix} |

| − | x & = & f(u, v) & = & \texttt{((u)(v))} | + | x & = & f(u, v) & = & \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} |

| − | \\ | + | \\[8pt] |

| − | y & = & g(u, v) & = & \texttt{((u,~v))} | + | y & = & g(u, v) & = & \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} |

| − | \end{ | + | \end{matrix}</math> |

|} | |} | ||

| − | The | + | The parenthetical expressions on the right are the cactus forms for the boolean functions that correspond to inclusive disjunction and logical equivalence, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the basic elements of the cactus notation for propositional logic. |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | {| align="center" border="1" cellpadding="8" cellspacing="0" style="text-align:center; width: | + | {| align="center" border="1" cellpadding="8" cellspacing="0" style="text-align:center; width:75%" |

| − | |+ <math>\text{Table 1. | + | |+ style="height:30px" | <math>\text{Table 1.} ~~ \text{Syntax and Semantics of a Calculus for Propositional Logic}\!</math> |

| − | |- style="background: | + | |- style="height:40px; background:ghostwhite" |

| − | | <math>\text{Expression}\!</math> | + | | <math>\text{Graph}\!</math> |

| + | | <math>\text{Expression}~\!</math> | ||

| <math>\text{Interpretation}\!</math> | | <math>\text{Interpretation}\!</math> | ||

| <math>\text{Other Notations}\!</math> | | <math>\text{Other Notations}\!</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <math> | + | | height="100px" | [[Image:Cactus Node Big Fat.jpg|20px]] |

| − | | <math>\operatorname{ | + | | <math>~</math> |

| + | | <math>\operatorname{true}</math> | ||

| <math>1\!</math> | | <math>1\!</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | | height="100px" | [[Image:Cactus Spike Big Fat.jpg|20px]] | ||

| <math>\texttt{(~)}</math> | | <math>\texttt{(~)}</math> | ||

| − | | <math>\operatorname{ | + | | <math>\operatorname{false}</math> |

| <math>0\!</math> | | <math>0\!</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <math>\ | + | | height="100px" | [[Image:Cactus A Big.jpg|20px]] |

| − | | <math> | + | | <math>a\!</math> |

| − | | <math> | + | | <math>a\!</math> |

| + | | <math>a\!</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <math>\texttt{( | + | | height="120px" | [[Image:Cactus (A) Big.jpg|20px]] |

| − | | <math>\operatorname{ | + | | <math>\texttt{(} a \texttt{)}~</math> |

| − | | | + | | <math>\operatorname{not}~ a</math> |

| − | <math>\ | + | | <math>\lnot a \quad \bar{a} \quad \tilde{a} \quad a^\prime</math> |

| − | |||

| − | \tilde{ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <math> | + | | height="100px" | [[Image:Cactus ABC Big.jpg|50px]] |

| − | | <math> | + | | <math>a ~ b ~ c</math> |

| − | | <math> | + | | <math>a ~\operatorname{and}~ b ~\operatorname{and}~ c</math> |

| + | | <math>a \land b \land c</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <math>\texttt{(( | + | | height="160px" | [[Image:Cactus ((A)(B)(C)) Big.jpg|65px]] |

| − | | <math> | + | | <math>\texttt{((} a \texttt{)(} b \texttt{)(} c \texttt{))}</math> |

| − | | <math> | + | | <math>a ~\operatorname{or}~ b ~\operatorname{or}~ c</math> |

| + | | <math>a \lor b \lor c</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <math>\texttt{( | + | | height="120px" | [[Image:Cactus (A(B)) Big.jpg|60px]] |

| + | | <math>\texttt{(} a \texttt{(} b \texttt{))}</math> | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | + | a ~\operatorname{implies}~ b | |

| − | \operatorname{ | + | \\[6pt] |

| + | \operatorname{if}~ a ~\operatorname{then}~ b | ||

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

| − | | <math> | + | | <math>a \Rightarrow b</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <math>\texttt{( | + | | height="120px" | [[Image:Cactus (A,B) Big ISW.jpg|65px]] |

| + | | <math>\texttt{(} a \texttt{,} b \texttt{)}</math> | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | + | a ~\operatorname{not~equal~to}~ b | |

| − | + | \\[6pt] | |

| + | a ~\operatorname{exclusive~or}~ b | ||

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | + | a \neq b | |

| − | + | \\[6pt] | |

| + | a + b | ||

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <math>\texttt{(( | + | | height="160px" | [[Image:Cactus ((A,B)) Big.jpg|65px]] |

| + | | <math>\texttt{((} a \texttt{,} b \texttt{))}</math> | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | + | a ~\operatorname{is~equal~to}~ b | |

| − | + | \\[6pt] | |

| + | a ~\operatorname{if~and~only~if}~ b | ||

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | + | a = b | |

| − | + | \\[6pt] | |

| + | a \Leftrightarrow b | ||

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <math>\texttt{( | + | | height="120px" | [[Image:Cactus (A,B,C) Big.jpg|65px]] |

| + | | <math>\texttt{(} a \texttt{,} b \texttt{,} c \texttt{)}</math> | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | \operatorname{ | + | \operatorname{just~one~of} |

| − | + | \\ | |

| − | \operatorname{is~false}. | + | a, b, c |

| + | \\ | ||

| + | \operatorname{is~false}. | ||

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | + | & \bar{a} ~ b ~ c | |

| − | + | \\ | |

| − | + | \lor & a ~ \bar{b} ~ c | |

| + | \\ | ||

| + | \lor & a ~ b ~ \bar{c} | ||

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <math>\texttt{(( | + | | height="160px" | [[Image:Cactus ((A),(B),(C)) Big.jpg|65px]] |

| + | | <math>\texttt{((} a \texttt{),(} b \texttt{),(} c \texttt{))}</math> | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | \operatorname{ | + | \operatorname{just~one~of} |

| − | + | \\ | |

| − | \operatorname{is~true}. | + | a, b, c |

| − | + | \\ | |

| − | \operatorname{ | + | \operatorname{is~true}. |

| − | \operatorname{into} | + | \\[6pt] |

| + | \operatorname{partition~all} | ||

| + | \\ | ||

| + | \operatorname{into}~ a, b, c. | ||

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | + | & a ~ \bar{b} ~ \bar{c} | |

| − | + | \\ | |

| − | + | \lor & \bar{a} ~ b ~ \bar{c} | |

| + | \\ | ||

| + | \lor & \bar{a} ~ \bar{b} ~ c | ||

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | | height="160px" | [[Image:Cactus (A,(B,C)) Big.jpg|90px]] | ||

| + | | <math>\texttt{(} a \texttt{,(} b \texttt{,} c \texttt{))}</math> | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | + | \operatorname{oddly~many~of} | |

| − | + | \\ | |

| − | + | a, b, c | |

| − | + | \\ | |

| − | + | \operatorname{are~true}. | |

| − | |||

| − | \operatorname{ | ||

| − | |||

| − | \operatorname{are~true}. | ||

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <p><math> | + | <p><math>a + b + c\!</math></p> |

<br> | <br> | ||

<p><math>\begin{matrix} | <p><math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | + | & a ~ b ~ c | |

| − | + | \\ | |

| − | + | \lor & a ~ \bar{b} ~ \bar{c} | |

| − | + | \\ | |

| + | \lor & \bar{a} ~ b ~ \bar{c} | ||

| + | \\ | ||

| + | \lor & \bar{a} ~ \bar{b} ~ c | ||

\end{matrix}</math></p> | \end{matrix}</math></p> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <math>\texttt{( | + | | height="160px" | [[Image:Cactus (X,(A),(B),(C)) Big.jpg|90px]] |

| + | | <math>\texttt{(} x \texttt{,(} a \texttt{),(} b \texttt{),(} c \texttt{))}</math> | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | \operatorname{ | + | \operatorname{partition}~ x |

| − | \operatorname{into} | + | \\ |

| − | + | \operatorname{into}~ a, b, c. | |

| − | \operatorname{ | + | \\[6pt] |

| − | \operatorname{species} | + | \operatorname{genus}~ x ~\operatorname{comprises} |

| + | \\ | ||

| + | \operatorname{species}~ a, b, c. | ||

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | + | & \bar{x} ~ \bar{a} ~ \bar{b} ~ \bar{c} | |

| − | + | \\ | |

| − | + | \lor & x ~ a ~ \bar{b} ~ \bar{c} | |

| − | + | \\ | |

| + | \lor & x ~ \bar{a} ~ b ~ \bar{c} | ||

| + | \\ | ||

| + | \lor & x ~ \bar{a} ~ \bar{b} ~ c | ||

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 397: | Line 413: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | The component notation <math>F = (F_1, F_2) = (f, g) : U^\ | + | The component notation <math>F = (F_1, F_2) = (f, g) : U^\bullet \to X^\bullet\!</math> allows us to give a name and a type to this transformation, and permits us to define it by means of the compact description that follows: |

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <math>\begin{ | + | <math>\begin{matrix} |

| − | (x, y) & = & F(u, v) & = & ( ~\texttt{((u)(v))}~ , ~\texttt{((u,~v))}~ ). | + | (x, y) & = & F(u, v) & = & ( ~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} ~,~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} ~ ). |

| − | \end{ | + | \end{matrix}</math> |

|} | |} | ||

| − | The information that defines the logical transformation <math>F\!</math> can be represented in the form of a truth table, as below. | + | The information that defines the logical transformation <math>F\!</math> can be represented in the form of a truth table, as shown below. |

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" cellspacing="0" style="border- | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" cellspacing="0" style="border-bottom:1px solid black; border-left:1px solid black; border-right:1px solid black; border-top:1px solid black; text-align:center; width:60%" |

| + | |- style="height:40px; background:ghostwhite; width:100%" | ||

| + | | style="width:25%" | <math>u\!</math> | ||

| + | | style="width:25%" | <math>v\!</math> | ||

| + | | style="width:25%; border-left:1px solid black" | <math>f\!</math> | ||

| + | | style="width:25%" | <math>g\!</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="border- | + | | style="border-top:1px solid black" | |

| − | | style="border- | + | <math>\begin{matrix} |

| − | | style="border- | + | 0 |

| − | + | \\[4pt] | |

| − | + | 0 | |

| − | + | \\[4pt] | |

| − | + | 1 | |

| − | | style="border- | + | \\[4pt] |

| − | + | 1 | |

| − | + | \end{matrix}</math> | |

| − | + | | style="border-top:1px solid black" | | |

| − | + | <math>\begin{matrix} | |

| − | | style="border- | + | 0 |

| − | + | \\[4pt] | |

| − | |- | + | 1 |

| − | | <math> | + | \\[4pt] |

| − | + | 0 | |

| − | | style="border-left:1px solid black" | <math> | + | \\[4pt] |

| − | + | 1 | |

| − | + | \end{matrix}</math> | |

| − | + | | style="border-top:1px solid black; border-left:1px solid black" | | |

| − | + | <math>\begin{matrix} | |

| − | | style="border- | + | 0 |

| − | + | \\[4pt] | |

| + | 1 | ||

| + | \\[4pt] | ||

| + | 1 | ||

| + | \\[4pt] | ||

| + | 1 | ||

| + | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

| + | | style="border-top:1px solid black" | | ||

| + | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| + | 1 | ||

| + | \\[4pt] | ||

| + | 0 | ||

| + | \\[4pt] | ||

| + | 0 | ||

| + | \\[4pt] | ||

| + | 1 | ||

| + | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

| + | |- style="height:40px; background:ghostwhite" | ||

| + | | style="border-top:1px solid black" | <math>u\!</math> | ||

| + | | style="border-top:1px solid black" | <math>v\!</math> | ||

| + | | style="border-top:1px solid black; border-left:1px solid black" | | ||

| + | <math>\texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))}\!</math> | ||

| + | | style="border-top:1px solid black" | | ||

| + | <math>\texttt{((} u \texttt{,} v \texttt{))}\!</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 442: | Line 486: | ||

A more complete framework of discussion and a fuller development of this example can be found in the neighborhood of the following site: | A more complete framework of discussion and a fuller development of this example can be found in the neighborhood of the following site: | ||

| − | :* [[ | + | :* [[Differential Logic and Dynamic Systems 2.0#Transformations of Type B2 .E2.86.92 B2|Transformations of Type '''B'''<sup>2</sup> → '''B'''<sup>2</sup>]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Consider the | + | Consider the ''transformation of textual elements'' (TOTE) in progress: |

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <math>\begin{ | + | <math>\begin{matrix} |

| − | x | + | x |

| − | \\ | + | & = & f(u, v) |

| − | y | + | & = & \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} |

| − | \\ | + | \\[8pt] |

| − | (x, y) & = & F(u, v) & = & ( ~\texttt{((u)(v))}~ , ~\texttt{((u,~v))}~ ) | + | y |

| − | \end{ | + | & = & g(u, v) |

| + | & = & \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} | ||

| + | \\[8pt] | ||

| + | (x, y) | ||

| + | & = & F(u, v) | ||

| + | & = & ( ~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} ~,~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} ~ ) | ||

| + | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Taken as a transformation from the universe <math>U^\ | + | Taken as a transformation from the universe <math>U^\bullet = [u, v]\!</math> to the universe <math>X^\bullet = [x, y],\!</math> this is a particular type of formal object, and it can be studied at that level of abstraction until the chickens come home to roost, as they say, but when the time comes to count those chickens, if you will, the terms of artifice that we use to talk about abstract objects, almost as if we actually knew what we were talking about, need to be fully fledged or fleshed out with extra ''bits of interpretive data'' (BOIDs). |

And so, to decompress the story, the TOTE that we use to convey the FOMA has to be interpreted before it can be applied to anything that actually puts supper on the table, so to speak. | And so, to decompress the story, the TOTE that we use to convey the FOMA has to be interpreted before it can be applied to anything that actually puts supper on the table, so to speak. | ||

| Line 469: | Line 517: | ||

When we consider a transformation in the alias interpretation, we are merely changing the terms that we use to describe what may very well be, to some approximation, the very same things. | When we consider a transformation in the alias interpretation, we are merely changing the terms that we use to describe what may very well be, to some approximation, the very same things. | ||

| − | For example, in some applications the discursive universes <math>U^\ | + | For example, in some applications the discursive universes <math>U^\bullet = [u, v]\!</math> and <math>X^\bullet = [x, y]\!</math> are best understood as diverse frames, instruments, reticules, scopes, or templates, that we adopt for the sake of viewing from variant perspectives what we conceive to be roughly the same underlying objects. |

When we consider a transformation in the alibi interpretation, we are thinking of the objective things as objectively moving around in space or changing their qualitative characteristics. There are times when we think of this alibi transformation as taking place in a dimension of time, and then there are times when time is not an object. | When we consider a transformation in the alibi interpretation, we are thinking of the objective things as objectively moving around in space or changing their qualitative characteristics. There are times when we think of this alibi transformation as taking place in a dimension of time, and then there are times when time is not an object. | ||

| − | For example, in some applications the discursive universes <math>U^\ | + | For example, in some applications the discursive universes <math>U^\bullet = [u, v]\!</math> and <math>X^\bullet = [x, y]\!</math> are actually the same universe, and what we have is a frame where <math>x\!</math> is the next state of <math>u\!</math> and <math>y\!</math> is the next state of <math>v,\!</math> notated as <math>x = u'\!</math> and <math>y = v'.\!</math> This permits us to rewrite the transformation <math>F\!</math> as follows: |

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <math>\begin{ | + | <math>\begin{matrix} |

| − | u' | + | u' |

| − | \\ | + | & = & f(u, v) |

| − | v' | + | & = & \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} |

| − | \\ | + | \\[8pt] |

| − | (u', v') & = & F(u, v) & = & ( ~\texttt{((u)(v))}~ , ~\texttt{((u,~v))}~ ) | + | v' |

| − | \end{ | + | & = & g(u, v) |

| + | & = & \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} | ||

| + | \\[8pt] | ||

| + | (u', v') | ||

| + | & = & F(u, v) | ||

| + | & = & ( ~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} ~,~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} ~ ) | ||

| + | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | All in all, then, we have three different ways in general of applying or interpreting a transformation of discourse, that we might sum up as one brand of alias and two brands | + | All in all, then, we have three different ways in general of applying or interpreting a transformation of discourse, that we might sum up as one brand of alias and two brands of alibi, all together, the ''Elseword'', the ''Elsewhere'', and the ''Elsewhen''. |

| − | of alibi, all together, the ''Elseword'', the ''Elsewhere'', and the ''Elsewhen''. | ||

No more angels on pinheads, the brass tacks next time. | No more angels on pinheads, the brass tacks next time. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Differential Analysis== |

It is time to formulate the differential analysis of a logical transformation, or a ''mapping of discourse''. It is wise to begin with the first order differentials. | It is time to formulate the differential analysis of a logical transformation, or a ''mapping of discourse''. It is wise to begin with the first order differentials. | ||

| − | We are considering an abstract logical transformation <math>F = (f, g) : [u, v] \to [x, y]</math> that can be interpreted in a number of different ways. Let's fix on a couple of major variants that might be indicated as follows: | + | We are considering an abstract logical transformation <math>F = (f, g) : [u, v] \to [x, y]\!</math> that can be interpreted in a number of different ways. Let's fix on a couple of major variants that might be indicated as follows: |

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{lccccc} | <math>\begin{array}{lccccc} | ||

| − | \text{Alias Map | + | \text{Alias Map} |

| − | \\ | + | & (x, y) |

| − | \text{Alibi Map | + | & = & F(u, v) |

| + | & = & ( ~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} ~,~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} ~ ) | ||

| + | \\[8pt] | ||

| + | \text{Alibi Map} | ||

| + | & (u', v') | ||

| + | & = & F(u, v) | ||

| + | & = & ( ~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} ~,~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} ~ ) | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 508: | Line 567: | ||

<math>F\!</math> is just one example among — well, now that I think of it — how many other logical transformations from the same source to the same target universe? In the light of that question, maybe it would be advisable to contemplate the character of <math>F\!</math> within the fold of its most closely akin transformations. | <math>F\!</math> is just one example among — well, now that I think of it — how many other logical transformations from the same source to the same target universe? In the light of that question, maybe it would be advisable to contemplate the character of <math>F\!</math> within the fold of its most closely akin transformations. | ||

| − | Given the alphabets <math>\mathcal{U} = \{ u, v \}</math> and <math>\mathcal{X} = \{ x, y \} | + | Given the alphabets <math>\mathcal{U} = \{ u, v \}\!</math> and <math>\mathcal{X} = \{ x, y \}\!</math> along with the corresponding universes of discourse <math>U^\bullet\!</math> and <math>X^\bullet = [\mathbb{B}^2],\!</math> how many logical transformations of the general form <math>G = (G_1, G_2) : U^\bullet \to X^\bullet\!</math> are there? |

| − | Since <math>G_1\!</math> and <math>G_2\!</math> can be any propositions of the type <math>\mathbb{B}^2 \to \mathbb{B},</math> there are <math>2^4 = 16\!</math> choices for each of the maps <math>G_1\!</math> and <math>G_2,\!</math> and thus there are <math>2^4 \cdot 2^4 = 2^8 = 256\!</math> different mappings altogether of the form <math>G : U^\ | + | Since <math>G_1\!</math> and <math>G_2\!</math> can be any propositions of the type <math>\mathbb{B}^2 \to \mathbb{B},\!</math> there are <math>2^4 = 16\!</math> choices for each of the maps <math>G_1\!</math> and <math>G_2,\!</math> and thus there are <math>2^4 \cdot 2^4 = 2^8 = 256\!</math> different mappings altogether of the form <math>G : U^\bullet \to X^\bullet.\!</math> |

| − | The set of all functions of a given type is customarily denoted by placing its type indicator in parentheses, in the present instance writing <math>(U^\ | + | The set of all functions of a given type is customarily denoted by placing its type indicator in parentheses, in the present instance writing <math>(U^\bullet \to X^\bullet) = \{ G : U^\bullet \to X^\bullet \},\!</math> and so the cardinality of this ''function space'' can most conveniently be summed up by writing: |

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | ||

| − | | <math>|(U^\ | + | | <math>|(U^\bullet \to X^\bullet)| ~=~ |(\mathbb{B}^2 \to \mathbb{B}^2)| ~=~ 4^4 ~=~ 256.\!</math> |

|} | |} | ||

| − | Given any transformation of this type, <math>G : U^\ | + | Given any transformation of this type, <math>G : U^\bullet \to X^\bullet,\!</math> the (first order) differential analysis of <math>G\!</math> is based on the definition of a couple of further transformations, derived by way of operators on <math>G,\!</math> that ply between the (first order) extended universes, <math>\mathrm{E}U^\bullet = [u, v, du, dv]\!</math> and <math>\mathrm{E}X^\bullet = [x, y, dx, dy],\!</math> of <math>G\text{'s}\!</math> own source and target universes. |

| − | differential analysis of <math>G\!</math> is based on the definition of a couple of further transformations, derived by way of operators on <math>G,\!</math> that ply between the (first order) extended universes, <math>\ | ||

| − | First, the ''enlargement map'' (or the ''secant transformation'') <math>\ | + | First, the ''enlargement map'' (or the ''secant transformation'') <math>\mathrm{E}G = (\mathrm{E}G_1, \mathrm{E}G_2) : \mathrm{E}U^\bullet \to \mathrm{E}X^\bullet\!</math> is defined by the following pair of component equations: |

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{lll} | <math>\begin{array}{lll} | ||

| − | \ | + | \mathrm{E}G_1 |

| − | \\ | + | & = & G_1 (u + \mathrm{d}u, v + \mathrm{d}v) |

| − | \ | + | \\[8pt] |

| + | \mathrm{E}G_2 | ||

| + | & = & G_2 (u + \mathrm{d}u, v + \mathrm{d}v) | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Second, the ''difference map'' (or the ''chordal transformation'') <math>\ | + | Second, the ''difference map'' (or the ''chordal transformation'') <math>{\mathrm{D}G = (\mathrm{D}G_1, \mathrm{D}G_2) : \mathrm{E}U^\bullet \to \mathrm{E}X^\bullet}\!</math> is defined in a component-wise fashion as the boolean sum of the initial proposition <math>G_j\!</math> and the ''enlarged'' or ''shifted'' proposition <math>\mathrm{E}G_j,\!</math> for <math>j = 1, 2,\!</math> in accord with following pair of equations: |

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{lllll} | <math>\begin{array}{lllll} | ||

| − | \ | + | \mathrm{D}G_1 |

| − | \\ | + | & = & G_1 (u, v) |

| − | + | & + & \mathrm{E}G_1 (u, v, \mathrm{d}u, \mathrm{d}v) | |

| − | \\ | + | \\[8pt] |

| − | \ | + | & = & G_1 (u, v) |

| − | \\ | + | & + & G_1 (u + \mathrm{d}u, v + \mathrm{d}v) |

| − | + | \\[8pt] | |

| + | \mathrm{D}G_2 | ||

| + | & = & G_2 (u, v) | ||

| + | & + & \mathrm{E}G_2 (u, v, \mathrm{d}u, \mathrm{d}v) | ||

| + | \\[8pt] | ||

| + | & = & G_2 (u, v) | ||

| + | & + & G_2 (u + \mathrm{d}u, v + \mathrm{d}v) | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Maintaining a strict analogy with ordinary difference calculus would perhaps have us write <math>\ | + | Maintaining a strict analogy with ordinary difference calculus would perhaps have us write <math>\mathrm{D}G_j = \mathrm{E}G_j - G_j,</math> but the sum and difference operations are the same thing in boolean arithmetic. It is more often natural in the logical context to consider an initial proposition <math>q,\!</math> then to compute the enlargement <math>\mathrm{E}q,</math> and finally to determine the difference <math>\mathrm{D}q = q + \mathrm{E}q,\!</math> so we let the variant order of terms reflect this sequence of considerations. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | = | + | Given these general considerations about the operators <math>\mathrm{E}\!</math> and <math>\mathrm{D},\!</math> let's return to particular cases, and carry out the first order analysis of the transformation <math>F(u, v) = ( ~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} ~,~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} ~ ).\!</math> |

| − | By way of getting our feet back on solid ground, let's crank up our current case of a transformation of discourse, <math>F : U^\ | + | By way of getting our feet back on solid ground, let's crank up our current case of a transformation of discourse, <math>F : U^\bullet \to X^\bullet,\!</math> with concrete type <math>[u, v] \to [x, y]\!</math> or abstract type <math>\mathbb{B}^2 \to \mathbb{B}^2,\!</math> and let it spin through a sufficient number of turns to see how it goes, as viewed under the scope of what is probably its most straightforward view, as an elsewhen map <math>F : [u, v] \to [u', v'].\!</math> |

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{ccc} | <math>\begin{array}{ccc} | ||

| − | + | u' & = & \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} | |

\\ | \\ | ||

| − | + | v' & = & \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} | |

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 572: | Line 636: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{c|cc} | <math>\begin{array}{c|cc} | ||

| − | t & | + | t & u & v \\[8pt] |

| − | + | 0 & 1 & 1 \\ | |

| − | 0 & | + | 1 & 1 & 1 \\ |

| − | 1 & | + | 2 & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel |

| − | 2 & | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 588: | Line 651: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{c|cc} | <math>\begin{array}{c|cc} | ||

| − | t & | + | t & u & v \\[8pt] |

| − | + | 0 & 0 & 0 \\ | |

| − | 0 & | + | 1 & 0 & 1 \\ |

| − | 1 & | + | 2 & 1 & 0 \\ |

| − | 2 & | + | 3 & 1 & 0 \\ |

| − | 3 & | + | 4 & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel |

| − | 4 & | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 600: | Line 662: | ||

In the upshot there are two basins of attraction, the state <math>(1, 1)\!</math> and the state <math>(1, 0),\!</math> with the orbit <math>(1, 1)\!</math> making up an isolated basin and the orbit <math>(0, 0), (0, 1), (1, 0)\!</math> leading to the basin <math>(1, 0).\!</math> | In the upshot there are two basins of attraction, the state <math>(1, 1)\!</math> and the state <math>(1, 0),\!</math> with the orbit <math>(1, 1)\!</math> making up an isolated basin and the orbit <math>(0, 0), (0, 1), (1, 0)\!</math> leading to the basin <math>(1, 0).\!</math> | ||

| − | + | On first examination of our present example we made a likely guess at a form of rule that would account for the finite protocol of states that we observed the system <math>X\!</math> passing through, as spied in the light of its boolean state variable <math>x : X \to \mathbb{B},\!</math> and that rule is well-formulated in any of these styles of notation: | |

| − | |||

| − | On first examination of our present example we made a likely guess at a form of rule that | ||

| − | would account for the finite protocol of states that we observed the system <math>X\!</math> passing through, as spied in the light of its boolean state variable <math>x : X \to \mathbb{B},</math> and that rule is well-formulated in any of these styles of notation: | ||

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{ll} | <math>\begin{array}{ll} | ||

| − | 1.1. & f : \mathbb{B} \to \mathbb{B} ~\text{such that}~ f : | + | 1.1. & f : \mathbb{B} \to \mathbb{B} ~\text{such that}~ f : x \mapsto \texttt{(} x \texttt{)} |

\\ | \\ | ||

| − | 1.2. & | + | 1.2. & x' ~=~ \texttt{(} x \texttt{)} |

\\ | \\ | ||

| − | 1.3. & | + | 1.3. & x ~:=~ \texttt{(} x \texttt{)} |

\\ | \\ | ||

| − | 1.4. & \ | + | 1.4. & \mathrm{d}x ~=~ 1 |

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 623: | Line 682: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{ll} | <math>\begin{array}{ll} | ||

| − | 2.1. & F : \mathbb{B}^2 \to \mathbb{B}^2 ~\text{such that}~ F : ( | + | 2.1. & F : \mathbb{B}^2 \to \mathbb{B}^2 ~\text{such that}~ F : (u, v) \mapsto ( ~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} ~,~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} ~ ) |

\\ | \\ | ||

| − | 2.2. & | + | 2.2. & u' ~=~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} \quad ~,~ \quad v' ~=~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} |

\\ | \\ | ||

| − | 2.3. & | + | 2.3. & u ~:=~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} \quad ~,~ \quad v ~:=~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} |

\\ | \\ | ||

| − | 2.4. & | + | 2.4. & ? |

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Well, the last one is not such a fall off | + | Well, the last one is not such a fall off a log, but that is exactly the purpose for which we have been developing all of the foregoing machinations. |

Here is what I got when I just went ahead and calculated the finite differences willy-nilly: | Here is what I got when I just went ahead and calculated the finite differences willy-nilly: | ||

| Line 639: | Line 698: | ||

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <math>\text{Orbit 1. Intitial Point :}~ (u, v) = (1, 1)</math> | + | | <math>\text{Orbit 1. Intitial Point :}~ (u, v) = (1, 1)\!</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{c|cc|cc|cc|cc|cc|c} | <math>\begin{array}{c|cc|cc|cc|cc|cc|c} | ||

| − | t & | + | t & u & v & \mathrm{d}u & \mathrm{d}v & \mathrm{d}^2 u & \mathrm{d}^2 v & \mathrm{d}^3 u & \mathrm{d}^3 v & \mathrm{d}^4 u & \mathrm{d}^4 v & \ldots \\[8pt] |

| − | + | 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \ldots \\ | |

| − | 0 & | + | 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \ldots \\ |

| − | 1 & | + | 2 & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & \ldots |

| − | |||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <math>\text{Orbit 2. Intitial Point :}~ (u, v) = (0, 0)</math> | + | | <math>\text{Orbit 2. Intitial Point :}~ (u, v) = (0, 0)\!</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{c|cc|cc|cc|cc|cc|c} | <math>\begin{array}{c|cc|cc|cc|cc|cc|c} | ||

| − | t & | + | t & u & v & \mathrm{d}u & \mathrm{d}v & \mathrm{d}^2 u & \mathrm{d}^2 v & \mathrm{d}^3 u & \mathrm{d}^3 v & \mathrm{d}^4 u & \mathrm{d}^4 v & \ldots \\[8pt] |

| − | + | 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & \ldots \\ | |

| − | 0 & | + | 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & 1 & \ldots \\ |

| − | 1 & | + | 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \ldots \\ |

| − | 2 & | + | 3 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \ldots \\ |

| − | 3 & | + | 4 & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & {}^\shortparallel & \ldots |

| − | 4 & | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 668: | Line 725: | ||

What we are looking for is — one rule to rule them all, a rule that applies to every state and works every time. | What we are looking for is — one rule to rule them all, a rule that applies to every state and works every time. | ||

| − | What we see at first sight in the tables above are patterns of differential features that attach to the states in each orbit of the dynamics. Looked at locally to these orbits, the isolated fixed point at <math>(1, 1)\!</math> is no problem, as the rule <math>\ | + | What we see at first sight in the tables above are patterns of differential features that attach to the states in each orbit of the dynamics. Looked at locally to these orbits, the isolated fixed point at <math>(1, 1)\!</math> is no problem, as the rule <math>\mathrm{d}u = \mathrm{d}v = 0\!</math> describes it pithily enough. When it comes to the other orbit, the first thing that comes to mind is to write out the law <math>\mathrm{d}u = v ~,~ \mathrm{d}v = \texttt{(} u \texttt{)}.\!</math> |

| − | == | + | ==Symbolic Method== |

It ought to be clear at this point that we need a more systematic symbolic method for computing the differentials of logical transformations, using the term ''differential'' in a loose way at present for all sorts of finite differences and derivatives, leaving it to another discussion to sharpen up its more exact technical senses. | It ought to be clear at this point that we need a more systematic symbolic method for computing the differentials of logical transformations, using the term ''differential'' in a loose way at present for all sorts of finite differences and derivatives, leaving it to another discussion to sharpen up its more exact technical senses. | ||

| Line 678: | Line 735: | ||

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <math>\begin{ | + | <math>\begin{matrix} |

| − | F & = & (f, g) & = & ( ~\texttt{((u)(v))}~ , ~\texttt{((u,~v))}~ ). | + | F & = & (f, g) & = & ( ~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} ~,~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} ~ ). |

| − | \end{ | + | \end{matrix}</math> |

|} | |} | ||

| − | In their application to this logical transformation the operators <math>\ | + | In their application to this logical transformation the operators <math>\mathrm{E}\!</math> and <math>\mathrm{D}\!</math> respectively produce the ''enlarged map'' <math>\mathrm{E}F = (\mathrm{E}f, \mathrm{E}g)\!</math> and the ''difference map'' <math>\mathrm{D}F = (\mathrm{D}f, \mathrm{D}g),\!</math> whose components can be given as follows. |

{| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{lll} | <math>\begin{array}{lll} | ||

| − | \ | + | \mathrm{E}f & = & \texttt{((} u + \mathrm{d}u \texttt{)(} v + \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))} |

| − | \\ | + | \\[8pt] |

| − | \ | + | \mathrm{E}g & = & \texttt{((} u + \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} v + \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))} |

| − | \\ | + | \\[8pt] |

| − | \ | + | \mathrm{D}f & = & \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} ~+~ \texttt{((} u + \mathrm{d}u \texttt{)(} v + \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))} |

| − | \\ | + | \\[8pt] |

| − | \ | + | \mathrm{D}g & = & \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} ~+~ \texttt{((} u + \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} v + \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))} |

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 700: | Line 757: | ||

But these initial formulas are purely definitional, and help us little to understand either the purpose of the operators or the significance of the results. Working symbolically, let's apply a more systematic method to the separate components of the mapping <math>F.\!</math> | But these initial formulas are purely definitional, and help us little to understand either the purpose of the operators or the significance of the results. Working symbolically, let's apply a more systematic method to the separate components of the mapping <math>F.\!</math> | ||

| − | A sketch of this work is presented in the following series of Figures, where each logical proposition is expanded over the basic cells <math>\texttt{ | + | A sketch of this work is presented in the following series of Figures, where each logical proposition is expanded over the basic cells <math>uv, u \texttt{(} v \texttt{)}, \texttt{(} u \texttt{)} v, \texttt{(} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{)}\!</math> of the 2-dimensional universe of discourse <math>U^\bullet = [u, v].\!</math> |

| − | ===Computation Summary | + | ===Computation Summary for Logical Disjunction=== |

| − | The venn diagram in Figure 1.1 shows how the proposition <math>f = \texttt{((u)(v))}</math> can be expanded over the universe of discourse <math>[u, v]\!</math> to produce a logically equivalent exclusive disjunction, namely, <math>\texttt{ | + | The venn diagram in Figure 1.1 shows how the proposition <math>f = \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))}\!</math> can be expanded over the universe of discourse <math>[u, v]\!</math> to produce a logically equivalent exclusive disjunction, namely, <math>uv + u \texttt{(} v \texttt{)} + \texttt{(} u \texttt{)} v.\!</math> |

| + | {| align="center" border="0" cellpadding="10" | ||

| + | | | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

o---------------------------------------o | o---------------------------------------o | ||

| Line 746: | Line 805: | ||

Figure 1.1. f = ((u)(v)) | Figure 1.1. f = ((u)(v)) | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | Figure 1.2 expands <math>\ | + | Figure 1.2 expands <math>\mathrm{E}f = \texttt{((} u + \mathrm{d}u \texttt{)(} v + \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))}\!</math> over <math>[u, v]\!</math> to give: |

| − | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center; width:100%" |

| − | | <math>\texttt{uv | + | | |

| + | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| + | \mathrm{E}\texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} | ||

| + | & = & uv \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u ~ \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | & + & u \texttt{(} v \texttt{)} \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))} | ||

| + | & + & \texttt{(} u \texttt{)} v \cdot \texttt{((} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{)} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | & + & \texttt{(} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{)} \cdot \texttt{((} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{)(} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))} | ||

| + | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | {| align="center" border="0" cellpadding="10" | ||

| + | | | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

o---------------------------------------o | o---------------------------------------o | ||

| Line 793: | Line 862: | ||

Figure 1.2. Ef = ((u + du)(v + dv)) | Figure 1.2. Ef = ((u + du)(v + dv)) | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | Figure 1.3 expands <math>\ | + | Figure 1.3 expands <math>\mathrm{D}f = f + \mathrm{E}f\!</math> over <math>[u, v]\!</math> to produce: |

| − | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center; width:100%" |

| − | | <math>\texttt{uv~ | + | | |

| − | |} | + | <math>\begin{matrix} |

| + | \mathrm{D}\texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} | ||

| + | & = & uv \cdot \mathrm{d}u ~ \mathrm{d}v | ||

| + | & + & u \texttt{(} v \texttt{)} \cdot \mathrm{d}u \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | & + & \texttt{(} u \texttt{)} v \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{)} \mathrm{d}v | ||

| + | & + & \texttt{(} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{)} \cdot \texttt{((} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{)(} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))} | ||

| + | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {| align="center" border="0" cellpadding="10" | ||

| + | | | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

o---------------------------------------o | o---------------------------------------o | ||

| Line 840: | Line 919: | ||

Figure 1.3. Df = f + Ef | Figure 1.3. Df = f + Ef | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| + | |} | ||

I'll break this here in case anyone wants to try and do the work for <math>g\!</math> on their own. | I'll break this here in case anyone wants to try and do the work for <math>g\!</math> on their own. | ||

| − | == | + | ===Computation Summary for Logical Equality=== |

| − | + | The venn diagram in Figure 2.1 shows how the proposition <math>g = \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))}\!</math> can be expanded over the universe of discourse <math>[u, v]\!</math> to produce a logically equivalent exclusive disjunction, namely, <math>uv + \texttt{(} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{)}.\!</math> | |

| − | |||

| − | The venn diagram in Figure 2.1 shows how the proposition <math>g = \texttt{((u,~v))}</math> can be expanded over the universe of discourse <math>[u, v]\!</math> to produce a logically equivalent exclusive disjunction, namely, <math>\texttt{ | ||

| + | {| align="center" border="0" cellpadding="10" | ||

| + | | | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

o---------------------------------------o | o---------------------------------------o | ||

| Line 889: | Line 969: | ||

Figure 2.1. g = ((u, v)) | Figure 2.1. g = ((u, v)) | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | Figure 2.2 expands <math>\ | + | Figure 2.2 expands <math>\mathrm{E}g = \texttt{((} u + \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} v + \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))}\!</math> over <math>[u, v]\!</math> to give: |

| − | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center; width:100%" |

| − | | <math>\texttt{uv | + | | |

| + | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| + | \mathrm{E}\texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} | ||

| + | & = & uv \cdot \texttt{((} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))} | ||

| + | & + & u \texttt{(} v \texttt{)} \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | & + & \texttt{(} u \texttt{)} v \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | & + & \texttt{(} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{)} \cdot \texttt{((} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))} | ||

| + | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | {| align="center" border="0" cellpadding="10" | ||

| + | | | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

o---------------------------------------o | o---------------------------------------o | ||

| Line 936: | Line 1,026: | ||

Figure 2.2. Eg = ((u + du, v + dv)) | Figure 2.2. Eg = ((u + du, v + dv)) | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | Figure 2.3 expands <math>\ | + | Figure 2.3 expands <math>\mathrm{D}g = g + \mathrm{E}g\!</math> over <math>[u, v]\!</math> to yield the form: |

| − | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center; width:100%" |

| − | | <math>\texttt{uv | + | | |

| + | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| + | \mathrm{D}\texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} | ||

| + | & = & uv \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | & + & u \texttt{(} v \texttt{)} \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | & + & \texttt{(} u \texttt{)} v \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | & + & \texttt{(} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{)} \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | {| align="center" border="0" cellpadding="10" | ||

| + | | | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

o---------------------------------------o | o---------------------------------------o | ||

| Line 983: | Line 1,083: | ||

Figure 2.3. Dg = g + Eg | Figure 2.3. Dg = g + Eg | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | == | + | ==Differential : Locally Linear Approximation== |

{| cellpadding="2" cellspacing="2" width="100%" | {| cellpadding="2" cellspacing="2" width="100%" | ||

| Line 1,005: | Line 1,106: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{lllll} | <math>\begin{array}{lllll} | ||

| − | F & = & (f, g) & = & ( ~\texttt{((u)(v))}~ , ~\texttt{((u,~v))}~ ) | + | F |

| + | & = & (f, g) | ||

| + | & = & ( ~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} ~,~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} ~ ) | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | To speed things along, I will skip a mass of motivating discussion and just exhibit the simplest form of a differential <math>\ | + | To speed things along, I will skip a mass of motivating discussion and just exhibit the simplest form of a differential <math>\mathrm{d}F\!</math> for the current example of a logical transformation <math>F,\!</math> after which the majority of the easiest questions will have been answered in visually intuitive terms. |

| − | For <math>F = (f, g)\!</math> we have <math>\ | + | For <math>F = (f, g)\!</math> we have <math>\mathrm{d}F = (\mathrm{d}f, \mathrm{d}g),\!</math> and so we can proceed componentwise, patching the pieces back together at the end. |

We have prepared the ground already by computing these terms: | We have prepared the ground already by computing these terms: | ||

| Line 1,018: | Line 1,121: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{lll} | <math>\begin{array}{lll} | ||

| − | \ | + | \mathrm{E}f & = & \texttt{((} u + \mathrm{d}u \texttt{)(} v + \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))} |

| − | \\ | + | \\[8pt] |

| − | \ | + | \mathrm{E}g & = & \texttt{((} u + \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} v + \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))} |

| − | \\ | + | \\[8pt] |

| − | \ | + | \mathrm{D}f & = & \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} ~+~ \texttt{((} u + \mathrm{d}u \texttt{)(} v + \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))} |

| − | \\ | + | \\[8pt] |

| − | \ | + | \mathrm{D}g & = & \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} ~+~ \texttt{((} u + \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} v + \mathrm{d}v \texttt{))} |

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | As a matter of fact, computing the symmetric differences <math>\ | + | As a matter of fact, computing the symmetric differences <math>\mathrm{D}f = f + \mathrm{E}f\!</math> and <math>\mathrm{D}g = g + \mathrm{E}g\!</math> has already taken care of the ''localizing'' part of the task by subtracting out the forms of <math>f\!</math> and <math>g\!</math> from the forms of <math>\mathrm{E}f\!</math> and <math>\mathrm{E}g,\!</math> respectively. Thus all we have left to do is to decide what linear propositions best approximate the difference maps <math>{\mathrm{D}f}\!</math> and <math>{\mathrm{D}g},\!</math> respectively. |

This raises the question: What is a linear proposition? | This raises the question: What is a linear proposition? | ||

| − | The answer that makes the most sense in this context is this: A proposition is just a boolean-valued function, so a linear proposition is a linear function into the boolean space <math>\mathbb{B}.</math> | + | The answer that makes the most sense in this context is this: A proposition is just a boolean-valued function, so a linear proposition is a linear function into the boolean space <math>\mathbb{B}.\!</math> |

| − | In particular, the linear functions that we want will be linear functions in the differential variables <math> | + | In particular, the linear functions that we want will be linear functions in the differential variables <math>\mathrm{d}u\!</math> and <math>\mathrm{d}v.\!</math> |

| − | As it turns out, there are just four linear propositions in the associated ''differential universe'' <math>\ | + | As it turns out, there are just four linear propositions in the associated ''differential universe'' <math>\mathrm{d}U^\bullet = [\mathrm{d}u, \mathrm{d}v].\!</math> These are the propositions that are commonly denoted: <math>{0, ~\mathrm{d}u, ~\mathrm{d}v, ~\mathrm{d}u + \mathrm{d}v},\!</math> in other words: <math>\texttt{(~)}, ~\mathrm{d}u, ~\mathrm{d}v, ~\texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)}.\!</math> |

| − | == | + | ==Notions of Approximation== |

{| cellpadding="2" cellspacing="2" width="100%" | {| cellpadding="2" cellspacing="2" width="100%" | ||

| Line 1,063: | Line 1,166: | ||

Justifying a notion of approximation is a little more involved in general, and especially in these discrete logical spaces, than it would be expedient for people in a hurry to tangle with right now. I will just say that there are ''naive'' or ''obvious'' notions and there are ''sophisticated'' or ''subtle'' notions that we might choose among. The later would engage us in trying to construct proper logical analogues of Lie derivatives, and so let's save that for when we have become subtle or sophisticated or both. Against or toward that day, as you wish, let's begin with an option in plain view. | Justifying a notion of approximation is a little more involved in general, and especially in these discrete logical spaces, than it would be expedient for people in a hurry to tangle with right now. I will just say that there are ''naive'' or ''obvious'' notions and there are ''sophisticated'' or ''subtle'' notions that we might choose among. The later would engage us in trying to construct proper logical analogues of Lie derivatives, and so let's save that for when we have become subtle or sophisticated or both. Against or toward that day, as you wish, let's begin with an option in plain view. | ||

| − | Figure 1.4 illustrates one way of ranging over the cells of the underlying universe <math>U^\ | + | Figure 1.4 illustrates one way of ranging over the cells of the underlying universe <math>U^\bullet = [u, v]\!</math> and selecting at each cell the linear proposition in <math>\mathrm{d}U^\bullet = [\mathrm{d}u, \mathrm{d}v]\!</math> that best approximates the patch of the difference map <math>{\mathrm{D}f}\!</math> that is located there, yielding the following formula for the differential <math>\mathrm{d}f.\!</math> |

| − | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center; width:100%" |

| − | | <math>\ | + | | |

| + | <math>\begin{array}{*{11}{c}} | ||

| + | \mathrm{d}f | ||

| + | & = & \mathrm{d}\texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} | ||

| + | & = & uv \cdot 0 | ||

| + | & + & u \texttt{(} v \texttt{)} \cdot \mathrm{d}u | ||

| + | & + & \texttt{(} u \texttt{)} v \cdot \mathrm{d}v | ||

| + | & + & \texttt{(} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{)} \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,~} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | {| align="center" border="0" cellpadding="10" | ||

| + | | | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

o---------------------------------------o | o---------------------------------------o | ||

| Line 1,109: | Line 1,222: | ||

Figure 1.4. df = linear approx to Df | Figure 1.4. df = linear approx to Df | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | Figure 2.4 illustrates one way of ranging over the cells of the underlying universe <math>U^\ | + | Figure 2.4 illustrates one way of ranging over the cells of the underlying universe <math>U^\bullet = [u, v]\!</math> and selecting at each cell the linear proposition in <math>\mathrm{d}U^\bullet = [du, dv]\!</math> that best approximates the patch of the difference map <math>\mathrm{D}g\!</math> that is located there, yielding the following formula for the differential <math>\mathrm{d}g.\!</math> |

| − | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="8" style="text-align:center; width:100%" |

| − | | <math>\ | + | | |

| + | <math>\begin{array}{*{11}{c}} | ||

| + | \mathrm{d}g | ||

| + | & = & \mathrm{d}\texttt{((} u \texttt{,} v \texttt{))} | ||

| + | & = & uv \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | & + & u \texttt{(} v \texttt{)} \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | & + & \texttt{(} u \texttt{)} v \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | & + & \texttt{(} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{)} \cdot \texttt{(} \mathrm{d}u \texttt{,} \mathrm{d}v \texttt{)} | ||

| + | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | {| align="center" border="0" cellpadding="10" | ||

| + | | | ||

<pre> | <pre> | ||

o---------------------------------------o | o---------------------------------------o | ||

| Line 1,156: | Line 1,280: | ||

Figure 2.4. dg = linear approx to Dg | Figure 2.4. dg = linear approx to Dg | ||

</pre> | </pre> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | Well, <math>g,\!</math> that was easy, seeing as how <math>\ | + | Well, <math>g,\!</math> that was easy, seeing as how <math>\mathrm{D}g\!</math> is already linear at each locus, <math>\mathrm{d}g = \mathrm{D}g.\!</math> |

| − | == | + | ==Analytic Series== |

| − | We have been conducting the differential analysis of the logical transformation <math>F : [u, v] \mapsto [u, v]</math> defined as <math>F : (u, v) \mapsto ( ~\texttt{((u)(v))}~, ~\texttt{((u, v))}~ ),</math> and this means starting with the extended transformation <math>\ | + | We have been conducting the differential analysis of the logical transformation <math>F : [u, v] \mapsto [u, v]\!</math> defined as <math>F : (u, v) \mapsto ( ~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{)(} v \texttt{))} ~,~ \texttt{((} u \texttt{,~} v \texttt{))} ~ ),\!</math> and this means starting with the extended transformation <math>\mathrm{E}F : [u, v, \mathrm{d}u, \mathrm{d}v] \to [u, v, \mathrm{d}u, \mathrm{d}v]\!</math> and breaking it into an analytic series, <math>\mathrm{E}F = F + \mathrm{d}F + \mathrm{d}^2 F + \ldots,\!</math> and so on until there is nothing left to analyze any further. |

| − | so on until there is nothing left to analyze any further. | ||