American Journals and the Strategic Bombing of Germany

- This article is published with "all rights reserved" by the author. You must obtain express written permission to copy or re-use this article.

Author: Gregory J. Kohs

- Emory University Honors paper, Dept. of History, 1990.

- Library holding: U4.5 .K65

- Emory University Honors paper, Dept. of History, 1990.

Introduction

The study of history is often an uplifting, enriching endeavor because it reveals the triumphs and glories of mankind. Not so the historical inspection of American strategic bombing of Germany during World War Two. Here is found the cold, calculating practice of administering destruction from the air. Undeniably, was presents to those involved a certain risk of death; however, it has long been accepted, or at least considered, that civilian populations should be spared from unrestricted battle action. Strategic bombing sidestepped these notions of military ethics and undercut those few people who questioned and opposed the practice. If the true horror of World War Two was the extent of people's systematic killing of other people, then strategic bombing in its magnitude and obduracy was no exception.

During the course of the war, Americans at home stayed informed of the happenings abroad through the media of letters from the front, newspapers, radio, newsreels, and popular news journals. Specifically, news magazines served the dual purpose of passing along first-rate information to the reader while maintaining a brief and entertaining format. Throughout the war, widely-read news journals generated a great amount of print concerning American strategic bombing. Reader's Digest, Life, Time, and Newsweek contained a rich sampling of articles addressing the bombing, complete with very telling opinions and conclusions. These magazines had enormous circulation rates and reached many American readers.

In addition to the larger news magazines, there were less-circulated liberal or intellectual magazines. These included periodicals like Atlantic Monthly, Harper's Magazine, Nation, and New Republic. Although these news journals were not as widespread, their readership was more select and probably more influential. Likewise, persuasive opinions were voiced in important articles. Contributing to another share of American readership were the journals Christian Century, Commonweal, Catholic World, and Christianity and Crisis. These publications held a distinctly religious view, so their readers understandably were partial to more ethical considerations.

Undoubtedly, average Americans relied heavily upon the popular magazine as a source of opinion, policy, and news from the fighting fronts. With such an important duty to fulfill, these magazines should have been reporting in a fair, honest, and principled manner. This study seeks to illuminate the portrayal of American strategic bombing that was offered the readership of the several journals cited above. It sets out to establish differences, if any, in the general expression of views concerning strategic bombing.

Several questions arise with respect to the presentation of the bombing picture. Just how was the bombing portrayed? Was it viewed as a war-winning and revolutionary weapons system, or simply as another routine method of making war? What military resullts were expected out of bombing? How was the thought of bombing civilians justified, or was squeamish hesitancy ignored and glossed over? What constituted military necessity in the age of total war, or more importantly, what was shown to constitute military necessity? Did the media report bombings as they were or as the media wished them to be seen? These pressing concerns demand answers.

The questions of the ethics of strategic bombing have been addressed now by historians and military theorists--but only seriously in the past ten or fifteen years. Many contemporary books and magazine articles have tackled these questions unequivocally. But why this lengthy span of time for a popular moral reassessment to take place? Did it take stalemate in Korea and defeat in Vietnam to jar the public's thinking? It actually may be more accurate to say that the morality of bombing was being questioned even during World War Two, but that the argument simply did not reach the masses. An examination of the appropriate magazines uncovers clues leading to a more complete analysis. This thesis attempts to show the true nature of the journal-media's representation of American strategic bombing in Europe.

A summary of this Honors Thesis is as follows. To begin, the work briefly outlines the history of the American strategic bombing campaign over Germany. Then follows a discussion of the moral viewpoints and ethical considerations concerning strategic bombing. After these introductory sections comes the heart of the paper: an analysis of the approach taken by American periodicals toward the air campaign in Europe. This will include the popular news journals, the smaller news journals, and the religious journals mentioned above. The research concludes with an association linking American public opinion with the magazines Americans read. This connection establishes the importance of this research because it will help to answer all of the questions heretofore raised. If American public opinion was misguided by improper reporting in popular journals, then these magazines must be held in some part responsible for the cheapening of American moral virtue.

America Bombs Germany

The story of aerial bombing operations over Europe consists primarily of three contrasting efforts: those executed by Germany (the Luftwaffe), by Great Britain (the R.A.F. Bomber Command), and by the United States (predominantly the Eighth Air Force). The year 1940 marked the trial and abandonment, both by the Germans and the British, of long-standing notions about strategic air power.

German lessons

The Germans learned serious lessons in target selection and aircraft construction. The first lesson was that the choice targets of Royal Air Force airfields and the seaport docks and shipping yards were too hastily forsaken for the urban areas of London and Coventry. Many scholars agree that England was virtually on the brink of strategic collapse due to Luftwaffe bombing attacks on airfields and ports, when German high command concluded that these attacks weren't having enough effect and switched to city bombing.

Concerning the second lesson, the Luftwaffe's medium-sized bombers were not sufficient to inflict the necessary damage that a strategic campaign supposedly required. This lack of heavy bombers was not the only handicap. The German bombers were not adequately armed with power-operated turrets.[1] In addition, their fighter escorts flew in close support rather than general support,[2] thus retarding the ability to dogfight against RAF fighters. Of course the Germans were not alone in committing crucial mistakes.

The British approach

Britain's Bomber Command tried in late 1939 to fly daylight precision bombing raids over Germany. Although pre-war theory stressed the invulnerability of bombers flying in close formation with guns blazing, the small-caliber armaments on the Whitley and Wellington bombers were not effective against Luftwaffe Me-109s coming from behind or across the beam.[3] The decision was made to switch to bombing specific oil and transportation facilities at night. However, the precision aspect of bombing went out the window. Bombers flying at night were often unable to hit a prescribed city, much less a specific factory or rail yard. With the failure of both daylight and nighttime precision raids, the British settled upon the practice of area bombing--that is, "dehousing and demoralizing" the German populace by placing bombs in a loose pattern on city centers. Aerial photographs were then taken in the summer of 1941. The results, compiled in the Butt Report, were disheartening. It was found that only 20% of the bombers were putting their payload within five miles of the target.[4] Nonetheless, the new bombing policy was staunchly adhered to under the guidance of Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris. The underlying fault with Harris' obstinacy was its rejection of traditional grand strategy:

Area attacks ... vitiated forces rather than concentrating them against a decisive point, they were uneconomical of force, and they strengthened the enemy will to resist and innoculated [sic] him against later onslaughts.[5]

So convinced of the correctness of their method, the British air authorities encouraged American leaders to adopt the area methodology. While Bomber Command went on its nightly raids, the world stood back to analyze, admire, or condemn the fires in the German cities.

American approach to bombing

The entry of the American Eighth Air Force in Europe was slow and staggered. The American force had no desire, at least initially, to join in on the night raids with the British. Instead, minor attacks were carried out against precision targets (usually railways, factories, and submarine pens)[6] in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. With their Norden bombsights American bombardiers wished to flaunt their daylight precision bombing technique, thoroughly practiced on the home front bombing ranges. However, the early needs of Operation TORCH in North Africa siphoned away many American bombers from the western European theater. After the Casablanca conference in January 1943, the Eighth was back in Britain ready to bomb "around-the-clock" with the RAF. The bloody RAF raid on Hamburg[7] was complemented by American daylight raids on July 25-26, 1943. Paying little attention to earlier British trials and errors, the American bomber leaders learned for themselves, quite senselessly, the same lessons their RAF counterparts had learned three years before.

The cloudy continental weather and the haze of the industrial Ruhr valley greatly reduced the Norden sight's accuracy. Also its necessity for a long straight approach to guarantee accuracy made the bomber more vulnerable to anti-aircraft fire (flak).[8] Because fighter escorts with acceptable ranges were not yet available, the lone B-17 and B-24 bombers in their stacked formations learned like the British that on-board defensive armament alone was simply not enough. The lack of insight was quick to show. On August 17, 1943, 315 B-17s made an attack on ball-bearing plants at Schweinfurt in which sixty Flying Fortresses were shot down.[9] A loss rate of 19% was clearly intolerable, but another raid on Schweinfurt was made on October 14. On this raid the bombers were incessantly harassed while out of fighter escort range, and 62 planes out of 228 were destroyed. The ratio was now up over one-in-four, and each Fortress carried ten men. The Eighth Air Force, for the time, had to give up any more raids of this type.

The invasion of Normandy brought about a new bombing priority: the rail lines of western France were to be cut in order to hinder German reinforcements being sent to the area come D-day. Unfortunately these stretches of track often came very close to urban populations, and the lives of the French citizens were overruled by military necessity. In April 1944, British and American bombs killed "250 people at Juvisy, 200 at Toulon, 500 at Lille, 850 at Rouen, and 650 at Paris."[10] The raids seemed to produce the desired effect, though, and the OVERLORD landing and COBRA breakout were made much easier. With the army's success on the ground, the Eighth returned to its bombing missions over Germany proper.

Transition from precision to area bombing

But the return was not quite the same. The nature of American bombing policy definitely changed in a two-step process. The first phase was a result primarily of General Eisenhower's changing position. Eisenhower stated, "While I have always insisted that U.S. Strategic Air Forces be directed against precision targets, I am always prepared to take part in anything that gives real promise to ending the war quickly."[11] This opened the door for new methods of bombing to be tested and tried. President Roosevelt himself summarized in August 1944 a common belief among military circles:

We have got to be tough with Germany, and I mean the German people not just the Nazis. ...It is of the utmost importance that every person in Germany should realize that this time Germany is a defeated nation. ...The German people as a whole must have it driven home to them that the whole nation has been engaged in a lawless conspiracy against the decencies of modern civilization.[12]

The first aerial consequence of this policy statement was Operation CLARION. This plan was drafted in December 1944 and was intended to break civilian morale by sending a wide series of low-level attacks across Germany. The targets were ostensibly transportation ones, but the real objective was the psychological collapse of the German populace at large. Small towns were hit later in 1945 in a deliberate attempt to bring home to the German citizen the omnipresence of the Allied air forces. CLARION was the call to arms for those military leaders who wished to move from the precise to the indiscriminate in bombing.

The second phase of the new American doctrine was evidenced in Operation THUNDERCLAP. It was a plan enacted in January 1945 which made Berlin, Leipzig, and Dresden acceptable, even preferred, targets. There was a two-fold reasoning behind THUNDERCLAP: one, that adding to the "existing pandemonium" would hasten the collapse and surrender of Germany and, two, that the Soviets would see for themselves the destructive power of the Anglo-American bomber forces.[13] Berlin was attacked on February 3 by some 900 B-17s. Some military objectives were hit, but 25,000 civilians may have perished.[14] Ten days later, historic Dresden was walloped by a two-day combined British and American raid which killed at least 30,000 civilians.[15] The American bombing policy over Germany had drastically changed and probably would have continued in this direction had the European war not ended. The ruthless attacks that summer on numerous Japanese cities lends credence to this assumption.

Outcomes of the campaigns

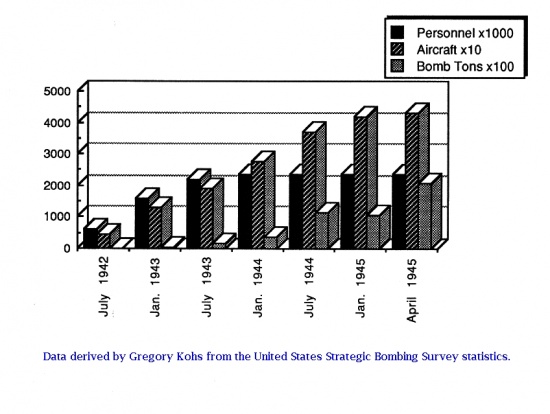

After about three years in Europe, American strategic air forces had developed into a gigantic operational group. At its maximum in August 1944, the U.S. Army Air Forces had over 619,000 combat personnel. These men dropped 1,461,864 tons of bombs on Germany.[16] Together with RAF Bomber Command's substantial efforts, 3,600,000 German dwelling units (20% of the total) were destroyed or heavily damaged. The homeless totaled between seven and eight million. Estimates suggest that 780,000 were wounded in bombing attacks and that 305,000 civilians were killed.[17] These are minimum figures, though. It has been proposed that more than 600,000 people in Germany were killed by "terror bombing".[18] The accompanying graphic, derived from United States Strategic Bombing Survey statistics, helps to illustrate the enormous increase in the American air infrastructure.

At what cost was this destruction achieved? Throughout the course of the air war against Germany, 9,949 American bomber planes were lost. This figure accounts for a significant fraction of the total number of bombers in action. It should be considered that with each lost bomber went not one engine, but usually four, not one man, but perhaps ten. In fact, 79,265 American aviators were lost in action[19] (more than 52,000 of them killed)[20] during bombing sorties. These fliers represented one of the most highly-trained and valuable segments of the military. Was their loss necessary?

Expectations and Ethics

A largely unanimous belief is found today that the American strategic bombing campaign in Europe neither lived up to military expectations nor maintained an ethical posture. Some dissension over these matters persists, but the facts argue in favor of the above. The pre-war expectation in the American ranks held that precision bombing would knock out certain key industries, thus crippling the Nazi war machine. The bomber was seen as a revolutionary means to replace old methods of war (land and sea), thereby shortening and ending war altogether. Founding these new beliefs was the Italian general Giulio Douhet who wrote many treatises on air power during the 1920's. In his The Command of the Air,[21] he outlined his basic tenet: wars of the future could be won by flying massive bombing strikes against enemy centers of production. These gigantic raids involving thousands of bomber aircraft would supposedly force the population to submit immediately to terms of peace.

Douhet, like so many other military theorists, understandably wished to avoid another war like the Great War. The senseless, bloody battles over a few hundred yards of "no man's land" nearly erased an entire generation from Europe's demography. Another trench-war stalemate was to be avoided at all costs. The solution seemed to be air power. There was a deep public fascination with the airplane, and it seemed a valiant, even humane, way to fight a war. Douhet's strategy, though, was primarily disregarded by military leaders and decision makers as too expensive and too risky. Wars had been fought with cannons and ships for so long that generals and admirals were unwilling to scrap these tried and true methods for an unproved one. General Billy Mitchell was the chief Douhetan advocate in America, and his voice ran into very stiff opposition and doubt. The idea that immense air strikes against enemy production centers could quickly win a war would have to wait until wartime to be implemented. The problem was that, in practice, the air raids were increased only gradually, not unleashed en masse at the dawn of war. Douhet's primary argument (sudden onslaught) was ignored in the hopes of building up bomber forces during the conflict.

This was an extravagant hope on which to pin so much trust. The steadily growing bomber forces failed to meet these overblown expectations. The simple fact was that American bomber units invested enormous effort to hit prescribed targets but then failed to follow up and hit them again to put them fully out of commission. Meanwhile, the British method of area bombing cities began to appear more attractive, albeit no more successful. Terror bombing of civilians produced not a breakdown but a stiffening of enemy resolve. The bomber proved to be an expensive way to kill people. On average, it took about three tons of bombs to kill one German.[22] The question "Was the bombing of civilians cost efficient?" is not the one that should be being asked, though.[23] The real question is whether this type of bombing was a legitimate means of fighting a war.

The killing of the innocent is unarguably wrong, yet the killing of an enemy directly involved in a war effort is sometimes justifiable.[24] This often unclear and imprecise line somewhere between ethical killing and unethical killing is the root of all argumentative objection to American strategic bombing. One would certainly balk at the thought of soldiers storming through a residential district, shooting everyone in sight, women and children. But notice that in warfare:

...war morality is not going to complain if the bombs dropped on a [munitions] plant destroy the plant and kill its workers inside -- or even outside while they are coming to or going from work. War morality would begin to complain if the attack on the workers were carried out in their homes... The problem with attacking workers in their homes is that that is where those not participating in the war (e.g., the children and old folks) also live.[25]

The Eighth Air Force would never admit that it was intentionally setting out to destroy homes, but the inaccuracy of the bombsight, the inclemency of the weather, and the broadening of the list of "acceptable" targets all served to make innocents into victims. Circumstances alone were not to blame for the haphazard bombing of civilians. The U.S. Army Air Force leaders'

'Official policy against indiscriminate bombing was so badly interpreted and so frequently breached as to become almost meaningless. ...In the end, both the policy and the apparent ethical support for it among AAF leaders turn out to be myths; while they contain elements of truth, they are substantially false or misleading.'[26]

Although the American bomber forces sought to distinguish between theirs and the British method, by the end of 1944 and early 1945, the distinction had all but disappeared.

The escalation from pure precision bombing to indiscriminate area bombing was almost inevitable. Due to the increasing dissatisfaction with the perceived lack of tangible and material results, precision bombing gave way to the bombing of civilians, which offered the alternative, if not nebulous, reward of disruption of enemy morale. At least with area bombing failure would be less appreciable.

In the new age of total war, the importance of enemy morale was heavily stressed by military theorists. Thus, it was felt that the collapse of German civilian morale might likewise bring about the collapse of the Nazi power structure. The fact that the British people and government did not falter during the Blitz was ignored. The fact that Nazi totalitarianism left little room for public interference in state and military matters was ignored. Morale simply seemed to be the last available "target", and it seemed imprudent not to try it.

In this slippery decline toward ruthless warmaking on civilians, no major political leaders or high-ranking military commanders paused to question seriously and oppose the direction in which bombing was headed. This is not to say that all sociopolitical figures and subordinate officers remained silent, but where it counted in the higher circles, little was said. "The moralists were certainly in the minority in those days."[27]

An interesting and quite valid interpretation of the wartime arguments over ethics suggests an overriding "unselfconsciousness" among the strategists, politicians, and military leaders.

Secure in their sense of having a job to do, no one appears to have questioned the relation between the carrying out of that job and the moral and political world-order in which the job was created.[28]

Both this lack of general reflection and the sense that bombing was a job or even a duty are further emphasized in that operational

...orders were usually little more than a statement of the objectives that had to be achieved, and of the means that would be provided to this end. From then on it was the business of the military.[29]

We know the means (strategic bombing, in all its forms), but what were the ends? "For the American forces, killing was sometimes an end in itself... It was connected in American minds to victory, however casually they measured it..."[30] Yet as brutal and cold as the militarists were, they almost had to be. And although they were not without blame, the significant portion of culpability need not rest on the generals' shoulders. Nor should the responsibility lie with the bomber crews themselves. At thirty thousand feet, the human effects of the raid are all but lost. This has been called an "ethics of altitude."

Where then lies the blame? Who should have been questioning the bombing practice? According to some ethicists, the job of criticism belongs to the community of scholars.[31] This is reasonable, but the academic community is in many ways a cloistered and insulated one. The age of total war immersed the general population in the fighting effort. Therefore, the relatively small segment of informed students of war could not be expected to educate the masses. That is a task better associated with the mass information media. I have chosen magazines as a focus of scrutiny because they reached the people, the people who fought the total war with their hands, their minds, and their sons and daughters. The lives of all those killed in the bombing campaign deserve the respect of this examination. A woman who lived through the fire raid of Hamburg said, "It was hell on earth. It was obvious that Hitler had to be destroyed, but did it have to be done this way?"[32]

Larger magazines

The first portion in the analysis of American periodicals covers those magazines with enormous circulation rates. The hands-down leader of these media giants was Reader's Digest. Because it then did not accept advertising, the Reader's Digest was not included in the standard directory's ranking by circulation,[33] but other sources show that the journal had a U.S. circulation of about 7,000,000 copies in 1944. The Reader's Digest was unique, though, in that its readership was much higher than its mere circulation rate.

In estimating the "readership" of their magazines most publishers like to apply a multiple of 3 or 4 to their circulation. The Digest can afford to be modest. It estimates its total readership at only 25,000,000. This is obviously very conservative. An estimate of double that number would probably be closer, since repeated surveys have shown that each issue is read both by more people and with greater thoroughness than is the case with most magazines.[34]

The Reader's Digest's immense size was primarily due to its popularity among average middle class America. It merits special scrutiny as the one journal uniquely able to steer popular opinion. Concerning strategic bombing in Europe, the Reader's Digest presented its view to the American public in a series of seven articles, two of which postdated the capitulation of Germany.

The first article was published in the September 1942 issue and is entitled "Can the RAF Keep It Up?"[35] It was written by Allan A. Michie, who is labeled as the author of Retreat to Victory and billed as a war correspondent for American magazines who specializes in covering RAF activities. Michie gave the RAF Bomber Command high marks; in fact, the next year Michie wrote The Air Offensive Against Germany,[36] in which he defends his belief that American bomber forces should abandon daylight bombing and join the British at night. His Digest article briefs the reader on the latest exploits of Bomber Command. Michie assures the public that even though the Luftwaffe failed to knock out Britain during the Blitz, the RAF would be capable of cracking the Nazis because of significant "differences in tactics, in quality and reserves of planes and personnel, and circumstances of the war itself."[37] Thus Michie disregards empirical evidence against bombing by claiming that the concentration and ability of the force has changed. He states, "The RAF has now perfected concentrated mass bombing to a fine art."[38] The Butt Report, which emphasized terrible inaccuracy, would certainly disagree. The author relates how Churchill once referred to the indiscriminate bombing of Berlin's citizens as "pleasure."

References

- ^ "The Uses of Air Power in 1939-1945", Sir Robert Saundby, excerpts from a lecture given on March 18, 1948, at London University, as condensed in The Aeroplane, April 16, 1948. (From Eugene M. Emme, ed., The Impact of Air Power (Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand Co., 1959), p. 218.)

- ^ "Strategic Air Power in the European War", General Carl A. Spaatz, from "Strategic Air Power: Fulfillment of a Concept", Foreign Affairs, April 1946. (From Eugene M. Emme, ed., The Impact of Air Power (Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand Co., 1959), p. 228.)

- ^ Robin Higham, Air Power: A Concise History, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1972), p. 131.

- ^ Lee Kennett, A History of Strategic Bombing, (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1982), p. 129.

- ^ Higham, Air Power, p. 132.

- ^ Kennett, History, p. 136.

- ^ Note: The city of Hamburg was devastated by the air raid. Over one million civilians fled the burning city; yet, 31,000 to 50,000 people unfortunate enough to remain were killed. The deaths were often due to asphyxiation, crushing, or intense burns and heat from the notorious fire storm which ensued.

- ^ Higham, Air Power, p. 133.

- ^ Note: Although 37?6 B-I7s were dispatched, only 315 made it to the target run. The raid also included an attack on the Messerschmitt factory at Regensburg.

- ^ Kennett, History, p. 156.

- ^ Ronald Schaffer, Wings of Judgment, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), p. 84.

- ^ Schaffer, Wings of Judgment, pp. 88-89.

- ^ Schaffer, Wings of Judgment, pp. 96.

- ^ Schaffer, Wings of Judgment, pp. 97.

- ^ Note: The casualties at Dresden were amplified by the large number of refugees seeking shelter from the advancing Red Army. The total death toll has never been undisputably established, and legitimate estimates range from 25,000 to about 100,000. Lee Kennett has stated (p. 161) that an estimate of 500,000 exists, but most scholars agree that that many bodies could not have been counted, much less disposed of by the authorities there.

- ^ Saundby, "The Uses", p. 225.

- ^ "Air Victory in Europe," excerpt from the Summary Report (European War) by the United States Strategic Bombing Survey, September 30, 1945. (From Eugene M. Emme, ed., The Impact of Air Power (Princeton, N J: D. Van Nostrand Co., 1959), p. 269.)

- ^ Ken Brown, "The Last Just War: How Just Was It?", The Progressive, August 1982, p. 19.

- ^ Saundby, "The Uses", p. 225.

- ^ Michael S. Sherry, The Rise of American Air Power, p. 204

- ^ Giulio Douhet, The Command of the Air, trans. Dino Ferrari (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1942).

- ^ Kennett, History, p. 182.

- ^ Michael Sherry, "The Slide To Total Air War", New Republic, 16 December 1981, p. 24. Note: Sherry frames a similar reasoning. He states, "...the usual questions we ask -- Was precision bombing more effective than area bombing? Was tactical bombing more useful than strategic? -- simply miss the point. We need to understand not why they failed to choose this or that alternative, but why they largely failed to weigh alternatives at all."

- ^ Jeffrie G. Murphy, "The Killing of the Innocent", in War, Morality, and the Military Profession, ed. Malham M. Wakin (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1986), pp. 341-64.

- ^ N. Fotion and G. Elfstrom, Military Ethics: Guidelines for Peace and War, (Boston: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1986), pp. 197-98.

- ^ Ronald Schaffer, "American Military Ethics in World War II: The Bombing of German Civilians", Journal of American History, LXVII, no. 2 (Sept. 1980), p. 319, as quoted in Kennett, History, p. 186.'

- ^ Solly Zuckerman, "Bombs and Morals", New Republic, 17 November 1986, p. 39.

- ^ Barrie Paskins and Michael Dockrill, The Ethics of War, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1979), p. 246.

- ^ Zuckerman, "Bombs and Morals", p. 42.

- ^ Sherry, "The Slide To Total Air War", p. 25.

- ^ Paskins and Dockrill, Ethics of War, p. 48.

- ^ Martin Middlebrook, "The Battle of Hamburg" (New York: Scribners, 1980), p. 338, as quoted in Kennett, History, p. 186.

- ^ The Ayer Directory of Publications (Philadelphia: IMS Press, 1944), p. 1189.

- ^ James Rorty, "The Reader's Digest: A study in cultural elephantiasis", Commonweal, 12 May 1940, p. 78.

- ^ Allan A. Michie, "Can the RAF Keep It Up?", Reader's Digest, September 1942, p. 26.

- ^ Allan A. Michie, The Air Offensive Against Germany (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1943).

- ^ Michie, "Can the RAF...", p. 26.

- ^ Michie, "Can the RAF...", p. 28.